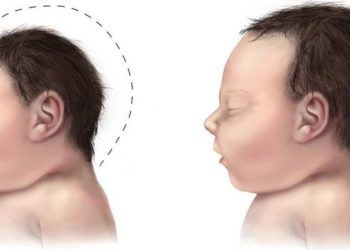

Microcephaly rates elevated in Brazil prior to Zika virus epidemic

1. In 2010, prior to the Zika virus epidemic, microcephaly rates were noted to be elevated in 2 Brazilian cities.

2. Microcephaly was associated with lack of maternal schooling, living without a partner, smoking during pregnancy, intrauterine growth restriction, vaginal delivery, and the pregnancy being the mother’s first.

Evidence Rating Level: 2 (Good)

Study Rundown: Though the recent Zika virus epidemic has led to concern about increased rates of microcephaly associated with the infection, data regarding baseline rates of microcephaly is lacking. To better understand the impact of ZIka, researchers in this study sought to determine the rates of microcephaly in 2 cities in Brazil prior to the epidemic. Using data from the 2010 birth cohort, researchers discovered the rates of both microcephaly and severe microcephaly were higher than expected for both cities, given previous estimates. Mothers who had received less than 11 years of schooling, those living without a companion, those who smoked during pregnancy, those for whom this was their first pregnancy, those who delivered vaginally, and those with infants with intrauterine growth restriction were more likely to have children with microcephaly. In one of the cities, delivery in a public hospital and alcohol consumption during pregnancy were also associated with an increased likelihood of microcephaly. Children born to mothers with a history of 5 or more previous deliveries were relatively protected against microcephaly. Though the data are limited in their generalizability given that only 2 cities were evaluated, the fact that microcephaly might be endemic to certain regions reveals the importance of continued exploration of causes of microcephaly, aside from Zika virus.

Click here to read the original article, published today in Pediatrics

Relevant Reading: Microcephaly in Brazil: how to interpret reported numbers?

In-Depth [cross-sectional study]: In this study, researchers used data from the Brazilian Ribeirão São Luís (SL) and Preto (RP) birth cohort studies to assess both rates of microcephaly and associated risk factors in each city. The cohorts included children born from January 2010 to December 2010, with 4220 live births in SL and 6174 live births in RP used in the final analysis. Microcephaly was classified using the INTERGROWTH-21st standards and the Brazilian Ministry of Health criterion and defined as head circumference (HC) >2 standard deviations (SDs) below the mean for gestational age (GA) and sex, and severe microcephaly defined as HC >3 SDs below the mean. The prevalence of microcephaly in SL was found to be 3.5%, as compared to 3.2% in RP when using only last normal menstrual period (LNMP) as the determiner of GA. However, when using either LNMP date or obstetrical ultrasound (OU), the prevalence of microcephaly was reduced in RP (2.5%). The rate of severe microcephaly was higher in SL (0.7%) when compared to RP (0.5%). Expected rates of microcephaly and severe microcephaly in an otherwise normal population are projected to be 0.55% and 0.14%, respectively. Maternal schooling between 5-8 years (OR 2.59, 95%CI: 2.08-3.22) and less than 4 years (OR 3.21 95%CI: 2.51-4.11), as well as vaginal delivery (OR 2.11, 95%CI: 2.10-2.11) and smoking in pregnancy (OR 1.86, 95%CI: 1.74-2.00) were all associated with increased risk of microcephaly.

Image: CC/Flickr/Brar_j

©2017 2 Minute Medicine, Inc. All rights reserved. No works may be reproduced without expressed written consent from 2 Minute Medicine, Inc. Inquire about licensing here. No article should be construed as medical advice and is not intended as such by the authors or by 2 Minute Medicine, Inc.

![Nanoparticle delivery of aurora kinase inhibitor may improve tumor treatment [PreClinical]](https://www.2minutemedicine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/20541_lores-350x250.jpg)