Patient Basics: Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery

Originally published by Harvard Health.

What Is It?

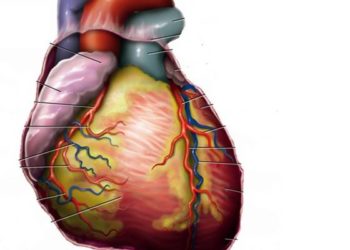

Coronary artery bypass surgery is a procedure that detours (or bypasses) blood around a blocked section of one or more coronary arteries. It is also called coronary artery bypass grafting or CABG (pronounced “cabbage”).

Coronary arteries are the blood vessels that supply the heart with oxygen and nutrients. You have several coronary arteries. They are named for their location. For example, your doctor may speak of the left main coronary artery, left anterior descending artery or the right coronary artery.

Coronary artery disease is any illness that damages these arteries. Coronary artery disease is often called “coronary atherosclerosis.” Atherosclerosis is the narrowing of arteries caused by the buildup of fat and cholesterol. This buildup is called plaque. Plaque can decrease the amount of blood that reaches the heart. The plaque can tear and cause a blood clot. The clot can block your artery and stop the flow of blood to your heart. This can cause a heart attack.

What It’s Used For

If you need surgery, it probably means that several of your coronary arteries are blocked and the blockages are widespread. The most common symptom of coronary artery disease is a type of chest pain called angina. This pain is usually described as a squeezing, pressing or burning pain in the center of the chest or just below the center of the rib cage. The pain may spread to the arms (especially the left), abdomen, lower jaw or neck.

Other symptoms of blocked coronary arteries may include:

- sweating

- nausea

- dizziness

- lightheadedness

- breathlessness

- palpitations

Some people mistake these symptoms for indigestion.

Some people with coronary artery disease do not have any symptoms. For them, the severe chest pain of a heart attack may be the first warning that blood flow to the heart has become critically low.

Sometimes, the location of the blockage makes bypass surgery the preferred treatment. If your doctor recommends surgery, he or she has probably considered other options. These can include drug therapy, balloon angioplasty and stents. The most likely factors pushing your doctor to recommend surgery are evidence that you have widespread coronary disease, or symptoms that you are experiencing that cannot be controlled with drugs.

How It’s Done

The surgeon uses a blood vessel from another part of your body to make a new channel so blood can flow around the blocked area of your artery or arteries. (Don’t worry: Removing arteries and veins won’t significantly affect the blood flow from where they’re taken.)

The blood vessel that will bypass your blockage comes from one of three places:

- The chest wall

An artery from inside the rib cage can be detached. The surgeon will sew the open end to the coronary artery below the blocked area. - The leg

A section of a long leg vein can be removed. One end is sewn onto the large artery that leaves the heart (the aorta). The other end is attached to the coronary artery below the blocked area. - The arm

A section of the radial artery in the forearm can be removed — as long as the ulnar artery (the other artery in the forearm) is functioning normally. One end is sewn onto the aorta. The other end is attached to the coronary artery below the blocked area.

Before the operation:

- Much of your body hair will be shaved, especially from your chest and legs.

- You’ll shower and wash with antiseptic soap to remove bacteria from your skin and reduce the chance of infection.

- You’ll be asked to give personal items, such as glasses, contact lenses, jewelry and dentures, to a family member for safekeeping.

- About an hour before surgery, you’ll receive medications to relax you and make you drowsy.

- You’ll be wheeled into the operating room and receive anesthesia to put you to sleep.

During the operation, the surgeon will usually connect you to a heart-lung machine. This machine controls your lungs and heart. It adds oxygen to your blood and circulates the blood throughout your body. The machine makes it possible for the surgeon to stop your heart from beating while he or she sews the new blood vessel in place.

The main steps of bypass surgery:

- Open the chest to reach the heart

- Remove the veins or arteries from the leg and/or arms that are needed for the operation

- Put the patient on the heart-lung machine and stop the heart with a solution that contains a large amount of potassium

- Perform the surgery

- Restart the heart (with an electric shock, if necessary) and disconnect the heart-lung machine

- Check, clean and close the surgical area

The surgery can take three to six hours. The time spent on the heart-lung bypass machine and making the bypass is much less — usually under an hour. The length of time depends on what has to be done. Each operation varies in complexity.

You may hear about several new techniques for bypass surgery. Port-access coronary bypass and minimally invasive coronary artery bypass are considered minimally invasive surgeries. This means they don’t involve opening the chest to the same degree that standard bypass surgery does. (This type of surgery is also called limited-access coronary artery surgery.) Another technique, called off-pump bypass surgery, is performed without stopping the heart. The goal of all these newer techniques is to decrease complications and/or pain.

Port-Access Coronary Artery Bypass

You’re placed on a heart-lung machine and your heart is stopped, just as it is during regular bypass surgery. But in this procedure, small incisions (called ports) are made in your chest, rather than cutting open the entire chest. The surgical team inserts instruments through the ports to perform the bypass. The team watches what is going on inside your chest on video monitors.

Minimally Invasive Coronary Artery Bypass

The goal of this technique is to avoid using the heart-lung machine. Instead, your heart continues to beat while the surgery is performed. This procedure also uses small ports in your chest, as well as a small incision directly over the coronary artery that needs to be bypassed. The surgeon can see the artery through this incision.

Off-Pump Coronary Artery Bypass

In this operation, the heart is never stopped. Special equipment holds the area of the heart on which the surgeon is working as still as possible. This technique is aimed at reducing complications, such as stroke, from using the heart-lung machine.

Follow-Up

After your surgery, you’ll be taken to a recovery area or intensive care unit. You’ll regain consciousness (wake up) after the anesthesia wears off. You may not be able to move your legs or arms at first, but your body and mind will soon become coordinated again. Your family may visit you briefly in the recovery area.

During your hospital stay, you’ll have tubes and wires attached to parts of your body. These give you drugs and fluids, withdraw blood samples and monitor your blood pressure. You’ll also have:

- One or more tubes in your chest. They drain fluid that builds up during and after the operation.

- Small patches or electrodes on your chest. They send information to monitors watched by the nursing staff.

- A tube in your mouth. This helps you breathe until you can breathe on your own. It is usually removed within 24 hours of the operation.

- A tube in your bladder. This drains urine until you can go to the bathroom on your own.

You’ll spend the first two or three days in the intensive care unit. When constant monitoring is no longer needed, you’ll be moved to a regular or transitional care unit.

Once your breathing tube is removed, you’ll be able to swallow liquids. You’ll begin a regular diet as soon as you feel up to it. You also can get out of bed, sit in a chair and walk around the room as soon as you are able. You can have sponge baths right away, and shower and shampoo in a few days.

Expect some discomfort in your chest where the incision was made. You’ll be given medication to relieve the pain. The incision in your chest and leg (if a vein was removed) also may feel itchy, sore, numb or bruised.

After surgery, you may develop a low-grade fever, which may cause heavy perspiration during the night or even during the day. This may last two or three days.

In the hospital, you’ll be told to practice deep breathing exercises and to cough. These are important to speed your recovery. Coughing reduces the chances of pneumonia and fever. Most patients are afraid to cough after surgery, but it won’t hurt your incision or the bypass. If you feel discomfort, hold a pillow over your chest. You also should change positions in bed often because lying on your back for long periods isn’t good for your lungs.

You’ll probably stay in the hospital four to six days. The length of time depends on your health before your surgery and whether you experience any complications afterward.

Once you are home, it usually takes a week to start to feel better. It’s common to feel weak when you return home. It will likely take another four to six weeks before you regain your energy level. You may experience:

- Decreased appetite. It could be several weeks before your appetite returns to normal.

- Leg swelling, if the graft was removed from your leg. You can reduce swelling by elevating your leg and wearing support stockings. Walking helps blood to circulate in your legs and also helps your heart.

- Difficulty sleeping. This will improve. Taking a pain pill before going to bed sometimes helps.

- Constipation. You may use a laxative. Be sure to add more fruit, fiber and juice to your diet.

- Mood swings. You’ll have good and bad days. Don’t become discouraged. Your mood will get better.

Your doctor will tell you what need immediate emergency attention, such as chest pain similar to the angina you had before surgery. The doctor also will tell you what complaints you should report to the doctor’s office, such as worsening ankle swelling or leg pain.

The American Heart Association recommends these guidelines for recovery at home:

- Get up at a normal hour.

- Bathe or shower if possible.

- Always dress in regular clothes.

- Rest in the mid-morning and mid-afternoon or after any activity.

- Take walks of a few blocks as permitted by your doctor.

- Remember that the ability to do more comes with time.

- Don’t lift objects weighing 5 pounds or more for at least four weeks after surgery. Your chest incision and breastbone need time to heal. You may, however, help with light housework. Don’t start heavier lifting without discussing this first with your doctor.

- You can go to the movies, church and out shopping.

- It’s best to wait a few weeks to drive, although you can be a passenger at any time.

You may resume sex four weeks after the operation.

When you return to work depends on how your recovery is going, the type of work you do and your age. If you have a sedentary job (such as sitting at a desk most of the day), you could return to work in four to six weeks. If you have a physically demanding job, you may have to wait longer — or, in some cases, find another type of work.

You may begin a cardiac rehabilitation program before you leave the hospital or up to 6 weeks after your discharge. After you leave the hospital, participating in a program usually requires a doctor’s referral. Most programs meet 3 or more times a week for 12 weeks. Each meeting lasts about an hour.

Surgery will improve blood flow to your heart, but it will not prevent coronary artery disease from coming back. You have to change your lifestyle to reduce this risk.

- If you smoke, stop — and avoid others’ tobacco smoke.

- If you have high blood pressure, have it treated.

- Lower your LDL cholesterol. You will probably need to take a statin drug.

- Eat more fruit, vegetables and fish.

- East less saturated fat and cholesterol.

- Exercise slowly build up to a total of 30 to 60 minutes for 3 or 4 days a week.

- Maintain a healthy weight. Your doctor can give you a weight range.

- If you have diabetes, keep it under control.

- Manage stress in your life. Try to avoid situations that you know may anger you.

Risks

One percent to 2% of people do not survive bypass surgery. When the operation is performed as an emergency, the death rate is even higher. Your risk depends on the condition of your heart, your age, the severity of other medical problems, and whether you have had a recent heart attack or other heart surgeries.

Other possible complications include:

- Internal bleeding

- Heart attack

- Heart failure

- Heart-rhythm disturbances

- Need for a permanent pacemaker

- Stroke

- Blood clots

- Wound infection

- Pneumonia

- Respiratory failure

- Kidney failure

- Fever and chest pain

- General risks from anesthesia

There is some concern that people who undergo bypass surgery may experience short- or long-term problems with memory, concentration and depression. Your surgeon will discuss the risks with you. You’ll need to sign a consent form to proceed with surgery.

Bypass surgery has been performed for more than 25 years. People in their 80s have had successful surgeries. On rare occasions, it has been performed on people in their 90s.

Here’s what you can do to reduce your risk of complications:

- If you still smoke, stop immediately.

- If you take aspirin or medications containing aspirin, ask your surgeon if you should stop taking them before surgery.

- Ask your doctor if you should keep taking your usual medications before surgery.

- Review your other medical problems and allergies with your doctor.

Your doctor will want you in the best possible condition before surgery. You also want to be sure you receive proper care while in the hospital.

Additional Info

American Heart Association (AHA)

7272 Greenville Ave.

Dallas, TX 75231

Toll-Free: 1-800-242-8721

www.americanheart.org

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)

P.O. Box 30105

Bethesda, MD 20824-0105

Phone: 301-592-8573

TTY: 240-629-3255

Fax: 301-592-8563

www.nhlbi.nih.gov/

American College of Cardiology

Heart House

2400 N Street NW

Washington, DC 20037

Phone: 202-375-6000

Toll-Free: 1-800-253-4636

www.acc.org

![Novel biodegradable sirolimus-eluting stents non-inferior to durable everolimus-eluting stents [BIOSCIENCE trial]](https://www.2minutemedicine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Taxus_stent_FDA-e1607803635904-350x250.jpg)