Patient Basics: Latex Allergy

Originally published by Harvard Health.

What Is It?

A latex allergy is a hypersensitivity to latex, which is a natural substance made of the milky sap of the rubber tree. Latex allergies arise when the immune system, which normally guards the body against bacteria, viruses and toxins, also reacts to latex. In any type of allergy, when the immune system reacts against an otherwise harmless substance, the substance is called an allergen.

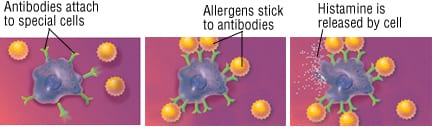

When the immune system detects the allergen, a type of antibody named immunoglobulin E (IgE) is produced, triggering the release of chemicals within the body. One chemical is histamine. Histamine is partly responsible for the redness, itching and swelling that can occur in the skin during an allergic reaction, and it produces symptoms of hives, rashes, a runny nose, and watery, swollen eyes. Histamine can also lead to breathing difficulties and a severe allergic reaction called anaphylaxis that can include a sudden drop in blood pressure, an increase in pulse, and tissue swelling.

Latex is a flexible, elastic and relatively inexpensive material used in a number of healthcare and consumer products. Because it forms an effective barrier against infectious organisms, latex is used to make hospital and medical items, such as surgical and examination gloves and some parts of anesthetic tubing, ventilation bags, respiratory tubing and intravenous (IV) lines. In addition, it is used in making countless consumer products, including balloons, condoms, diaphragms, rubber gloves, tennis shoe soles, nipples for baby bottles and pacifiers, toys, rubber hoses and tires. Seven million metric tons of latex are used in manufacturing each year.

As the use of latex products increases, so does the incidence of latex allergies. Latex examination gloves are used routinely when health care workers do procedures or handle body fluids. Because of their exposure to latex, health care workers are at increased risk of developing a hypersensitivity to latex products.

In addition to workers whose occupations expose them to latex, people who undergo repeated surgical procedures can develop latex allergies. For example, children born with the birth defect called spina bifida are usually exposed repeatedly to latex products because they need a series of medical and surgical procedures. About 50% of children with spina bifida develop a latex allergy.

People can become sensitized to latex as a result of direct contact with natural rubber products. Inhaling latex particles is a common way for health care workers to become sensitized to latex. Many medical gloves are coated with cornstarch to make them easier to pull on and off. Cornstarch absorbs the latex proteins, and then carries them into the air where they can be inhaled.

Symptoms

As with any type of allergy, the first exposure to latex allergens usually does not cause any reaction. However, this first exposure can sensitize the immune system to the allergen, which can cause symptoms after later exposures.

When the sensitivity is to a chemical additive used in manufacturing rubber latex, the reaction typically occurs one to two days after exposure and usually involves a form of contact dermatitis, a rash that resembles poison ivy. The skin is usually red, cracked and blistered.

When the sensitivity is to the latex protein, more serious symptoms can occur within minutes of exposure. Symptoms include hives, runny nose (allergic rhinitis) and allergic asthma. In rare instances, this type of allergy can cause anaphylaxis, a severe allergic reaction that can include a sudden drop in blood pressure, an increase in pulse, difficulty breathing and tissue swelling. Without prompt and proper treatment, anaphylaxis can lead to unconsciousness and, rarely, death.

Diagnosis

Your doctor may suspect that your symptoms are related to a latex sensitivity if you have a history of exposure followed rapidly by the appearance of symptoms. If you have other allergies and allergic conditions, you may be more susceptible to latex allergy. Examples of allergic conditions are asthma, hay fever or eczema (atopic dermatitis). There also seems to be a link between latex allergies and allergies to certain foods: avocados, bananas, kiwi, pineapples, tomatoes and chestnuts.

Along with your exposure history, a blood test called RAST can help to determine your sensitivity to latex. The RAST measures the amount of latex-associated IgE antibodies in your blood. Skin testing for latex allergy also can be done. In some cases, challenge tests with latex products are used to confirm the diagnosis. In a challenge test, you stay away from the suspected allergen for a period of time, then are exposed to the substance to see if you develop symptoms.

Prevention

The best way to prevent any type of allergy is to avoid exposure. With latex allergies, that means using gloves not made of latex for dishwashing or other chores, refraining from blowing up balloons, avoiding rubber bands and using condoms made of materials other than latex. You also should tell your health care providers so that they can avoid exposing you to products that contain latex. But if you work in the health care field, avoiding latex can be trickier. Many medical products contain latex. Although you may not be able to avoid latex completely, you may be able to limit the use of latex products and find products that are less irritating.

The amount of latex allergens shed by different types of gloves, for example, varies tremendously. Some contain less of the chemical additives that have been shown to cause skin sensitivity. A number of successful lawsuits involving latex reactions have prompted many manufacturers to change the way they make latex products. Because latex gloves that are powdered with cornstarch appear to cause the most problems, using gloves that are not powdered may help to prevent reactions.

Treatment

The most important treatment for occupational latex allergies is to avoid repeat exposures, because repeated exposures can increase sensitivity. People with latex allergy may need to be reassigned to different work duties or may need to change occupations.

Once you have a reaction to latex, treatment depends on the type and severity of your reaction. An antihistamine can block the actions of histamine, so an antihistamine can decrease itching and swelling. Corticosteroid drugs, which are powerful anti-inflammatory agents, are used for more severe symptoms. These are available as tablets, nasal or bronchial sprays or topical creams. Although corticosteroid medications can be very effective against allergic reactions, they can produce serious side effects when used in high dosages or over long periods of time. Your doctor will weigh the benefits against the risks of side effects, using corticosteroids in the lowest dose that works for you if you need them.

Anaphylaxis, the most serious allergic reaction, can cause blood vessels to dilate and air passages of the lungs to narrow, leading to wheezing, breathing difficulties and a drop in blood pressure. In the most severe cases, loss of consciousness and death can occur. Anaphylaxis requires an emergency injection of epinephrine (adrenaline) and treatment with intravenous fluids.

If you have a latex allergy, consider carrying an emergency epinephrine kit.

When To Call A Professional

If you suspect a latex allergy, you need a medical evaluation.

If you experience difficulty breathing, a rapid pulse, facial swelling or dizziness, contact your doctor or go to an emergency room at once. These symptoms could signal anaphylaxis, which requires emergency treatment.

Prognosis

With prompt, appropriate treatment, most people recover completely from an allergic reaction to latex. In rare cases, an allergic reaction to latex can be severe, leading to anaphylaxis and death. If latex is strictly avoided, the allergy reaction will not occur.

Additional Info

American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI)

555 East Wells St.

Suite 1100

Milwaukee, WI 53202-3823

Phone: (414) 272-6071

Toll-Free: (800) 822-2762

http://www.aaaai.org/

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

4676 Columbia Parkway

Mail Stop C-18

Cincinnati, OH 45226

Toll-Free: (800) 356-4674

Fax: (513) 533-8573

http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/