Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight: not so clear [NEJM]

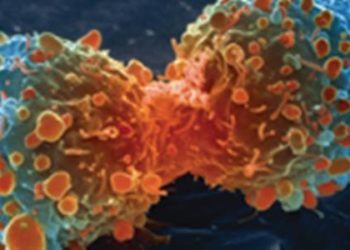

Image: CC/DCJohn

Key study points:

1. Overall study population didn’t show a difference in BMI at 2 years if they used noncaloric drinks instead of sugar-sweetened beverages, despite showing a difference at the 1 year mark

2. The Hispanic subset of the subjects did show a difference in BMI at both 1 and 2 years

Primer: The rise of obesity in the United States has been temporally associated with an increase in the use of sugar-sweetened drinks by adolescents. This association has brought into question the role of sugar-sweetened drinks in the likelihood of obesity, especially because many adolescents consume about 300 kcal per day, or 15% of total energy intake, through these products. Previously, findings from randomized controlled trials were inconclusive and public health measures aimed at reducing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages are still controversial.

This [retrospective] study: 224 overweight or obese adolescents were randomly assigned into two groups: one who would continue to consume sugar-sweetened beverages and one that would spend the next 2 years consuming non-caloric beverages at home. All subjects were previously consuming an average of 1.7 servings a day of sugar-sweetened drinks. The goal was to find if the groups had different rates of change in weight. The primary endpoint was the change in body mass index after 2 years, which was not significantly different between the experimental and controls groups in this study (change in experimental minus control group: -0.3, p=0. 46). At one year, there were differences in BMI between the two groups (-0.57, p=0.045). Among the participants, 27 were Hispanic in the experimental group and 19 in the control group. This subset of patients did have significant inter-group BMI differences in both years 1 (−1.79, P=0.007) and 2(−2.35, P=0.01). No adverse events were reported.

In sum: This study didn’t find a difference in the experimental and control groups by comparing BMIs, despite being able to successfully decrease the sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in the experimental group down to zero. They also found effect modification through the Hispanic group, which was the only group to have lower BMI scores on average at both 1 and 2 years as compared to the control group. It is still unclear whether the difference in effect at 1 and 2 years could be due to increase sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in the experimental group. Strengths of the trial include a diverse patient population, home-centered dietary behavior changes.

One major limitation of this study is that the experimental group was dependent on the consistent delivery of the non-caloric beverages, and had additional support through regular check-ins, mailed-in reminders about healthy beverage consumption, etc. These measures are difficult to recreate in real life without the benefit of a study and therefore make this study’s results more difficult to reproduce. Moreover, the authors’ reliance on self-reporting of dietary intake by the participants probably predisposes to underreporting, which could have played a significant role in the final results, especially between years 1 and 2.

It is unclear what, if any, role this study will have in the development of public policy centered around the decreased consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages.

By David Mattos and Marc Succi

Click to read the study in NEJM

© 2012 2minutemedicine.com. All rights reserved. No works may be reproduced without written consent from 2minutemedicine.com. DISCALIMER: Posts are not medical advice and are not intended as such. Please see a healthcare professional if you seek medical advice.